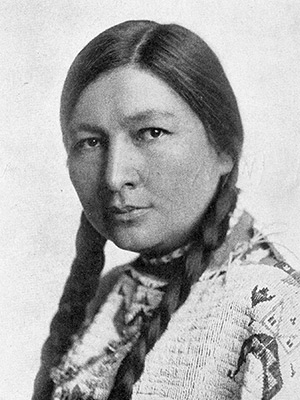

Zitkála-Šá

Zitkála-Šá, Red Bird was born on the Yankton Indian Reservation in South Dakota on February 22, 1876. A member of the Yankton Dakota Sioux, she was raised by her mother after her father abandoned the family. Her mother brought up the children in traditional Indian ways.

When she was eight years old, Quaker missionaries visited the Reservation, taking several of the children (including Zitkála-Šá) to Wabash, Indiana to attend White’s Indiana Manual Labor Institute.

Zitkála-Šá left despite her mother’s disapproval. At this residential school, Zitkála-Šá was given the missionary name Gertrude Simmons. She attended the Institute until 1887. She was conflicted about the experience and wrote both of her great joy in learning to read and write and play the violin, as well as her deep grief and pain of losing her heritage by being forced to pray as a Quaker and cut her hair.

She returned to the reservation but was culturally unhinged, “neither a wild Indian nor a tame one,” as she described herself later in The School Days of an Indian Girl. After four unhappy years, she returned to her Quaker missionary school and graduated. Though her mother wanted her to return home after graduation, Zitkála-Ša chose to attend Earlham College in Richmond, Indiana, where she had been offered a scholarship.

It was while at Earlham that she began to collect stories from Native tribes. She translated the stories into Latin and English. In 1897, just six weeks before she was to graduate, Zitkála-Šá had to leave Earlham because of financial and health issues. Again, she chose not to return to the Reservation. Instead, she moved to Boston, where she studied violin at the New England Conservatory of Music.

Having become an accomplished violinist in 1899, she took a job as a music teacher at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania. Meanwhile, the estrangement from her mother and the old ways of the reservation had grown, as had her resentment over the treatment of American Indians by the state, church, and population at large.

Around 1900, she began to express her feelings publicly in writing. Zitkála-Ša struggled with the issues of cultural dislocation and injustice – which brought suffering to her people. But, her authorial voice was not merely critical. She was earnestly committed to being a bridge-builder between cultures.

In 1901, Zitkála-Ša was dismissed from Carlisle after publishing an article in Harper’s Monthly describing the profound loss of identity felt by an American Indian boy after undergoing assimilationist education at the school.

That year Zitkála-Šá returned to the Yankton Reservation to care for her ailing mother. She was also gathering material for her collection of traditional Sioux stories to publish in Old Indian Legends, commissioned by the Boston publisher Ginn and Company.

Later that year she accepted a job as a clerk at the Bureau of Indian Affairs office at Standing Rock Indian Reservation. It is there in 1902 she met and married her husband, Raymond T. Bonnin, who was also employed by the Indian Agency. Soon after their marriage, Bonnin was assigned by the BIA to the Uintah-Ouray reservation in Utah. The couple lived and worked there with the Ute people for the next fourteen years. During this period, Greta gave birth to the couple’s only child, Alfred Ohíya Bonnin. It was here that Bonnin became affiliated with the Society of American Indians. Bonnin was elected secretary of the Society in 1916, and moved to Washington, DC, where she worked with the Society and edited the American Indian Magazine.

In 1926, she founded the National Council of American Indians and continued to pursue reforms through public speaking and lobbying efforts. She was instrumental in the passage of the Indian Citizenship Bill and secured powerful outside interests in Indian reform.

Bonnin died in Washington, DC in 1938 and was buried in Arlington Cemetery. Her autobiographical work makes her perhaps the first American Indian woman to write her own story without the aid of an editor, interpreter, or ethnographer.