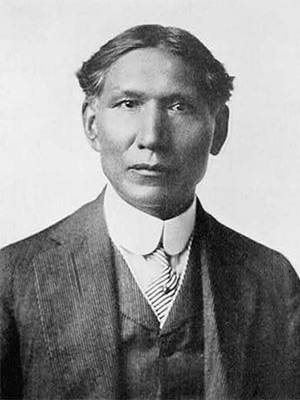

Dr. Charles A. Eastman

Charles Alexander Eastman was born near Redwood Falls, Minnesota in the winter of 1858. At birth, he was named Hakadah – the pitiful last – because he was the last of five children born to Wakantakawin, his mother, who died shortly after his birth. His mother Wakantakawin (aka Mary Nancy Eastman) was the granddaughter of the Chief Cloud Man and the daughter of Stands Sacred and a well-known army officer, Seth Eastman a U.S. Army officer stationed at Fort Snelling.

In the Dakota tradition of naming to mark life passages, Hakadah was later named Ohíyesa – the Winner. During the Dakota War of 1862, Ohíyesa was separated from his father, Wak-anhdi Ota, and siblings, and they were thought to have died. His maternal grandmother Stands Sacred (Wakháŋ Inážiŋ Wiŋ) and her family took the boy with them as they fled from the warfare into North Dakota and Manitoba.

For the next 11 years, Eastman lived the original nomadic life of his people with his uncle and grandmother. His uncle was a well-known hunter and warrior and gave Ohíyesa the traditional training of a young hunter, warrior, and member of the tribe. Ohíyesa’s knowledge of these skills and spiritual values would later be reflected in his activities and his writings.

Ohíyesa was later reunited with his father and oldest brother John in South Dakota. His father had converted to Christianity, after which he took the name of Jacob Eastman. John also converted and took the surname Eastman.

Eastman’s father strongly supported his sons getting an education in European-American-style schools so Ohíyesa was sent to Flandreau Indian School and thus was abruptly introduced into an alien society that he would struggle to understand for the rest of his life. His father prevailed and Ohíyesa began to adopt the ways of white civilization accepting Christianity and taking the name Charles Alexander Eastman.

Despite his unhappiness, Eastman applied himself to his studies in school. Two years later, he walked 150 miles to attend a better school at Santee, Nebraska, where he excelled. He was soon accepted to the preparatory department of Beloit College in Wisconsin.

Known as Charles Eastman now, he spent two years at Beloit before moving on to Dartmouth College, graduating in 1887. Eastman then enrolled as a medical student at Boston University. He graduated in 1890 with his medical degree and the honor of being the orator of his class. He had spent a total of 17 years in primary, secondary, college, and professional education, much less time than is usually required for most students.

Eastman wanted to give back to his community as a physician, so he applied to the Bureau of Indian Affairs and received an appointment to Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota. At Pine Ridge, he met Elaine Goodale, a teacher and published author, and they were married in 1891.

Eastman arrived at Pine Ridge in November 1890, just before the massacre of Lakota people at Wounded Knee on December 29. As the reservation’s resident physician, he provided medical assistance to the massacre’s few survivors and found his confidence in white culture severely shaken. Eastman’s time at Pine Ridge was troubled overall and lasted only until 1893, when he left because of conflict with the Indian agent.

Eastman and his wife then moved to St. Paul, where he attempted to set up a private medical practice. Unsuccessful, he took a job with the YMCA as supervisor of their Native programs in the western United States and Canada.

He tried reservation medical practice again in 1900, at Crow Creek Reservation, but resigned after only two years due to conflict with his supervisors. In 1903, he was offered another job within the Indian service: to assist Dakota in establishing family names that would translate well into English and could be used legally. He continued this work for six years.

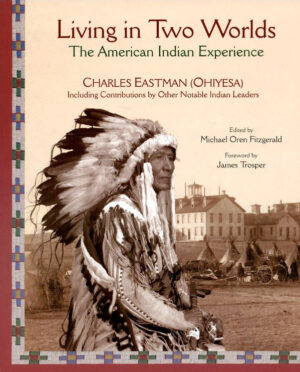

In 1902, Eastman became a published author. His first book, Indian Boyhood, is a compilation of stories he had been telling his own children about his childhood. The book was immediately popular. Encouraged by its success, Eastman continued to write for children and adults. He published thirteen books in all, two co-written with his wife, who served as his editor.

Largely because of his publishing success, Eastman became a noted speaker and traveled widely. In 1910, he took a job with the Boy Scouts of America as their American Indian advisor. Inspired by this experience, he opened a summer camp for children in New Hampshire that he and his family ran from 1915 to 1921.

In 1921, Eastman and his wife permanently separated. During the remaining eighteen years of his life, Eastman continued to lecture but no longer published. He increasingly withdrew from white society, building himself a small cabin in the woods of upstate New York, where he spent most of his time.

He died of heart failure in 1939 while visiting his son, also named Ohíyesa, in Detroit, Michigan.