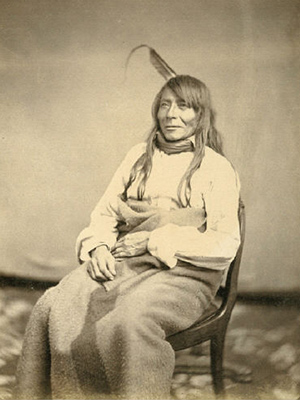

Struck by the Ree

The first of 15 Indian names on the Treaty of 1858, which made the settlement of Yankton possible, was Pa-la-ne-a-pa-pe (The Man That Was Struck by the Ree). His mark was followed by those of Smutty Bear, Charles F. Picotte, Crazy Bull, Iron Horn, One That Knocks Down Two, Fast Bull, Walking Elk, Standing Elk, the Elk With the Bad Voice, Grabbing Hawk, Owl Man, White Medicine Cow That Stands, Little White Swan and Pretty Boy.

Separating fact from fiction, however, about the Yankton’s principal leader continues to be a dilemma for historians.

Legend says as a boy, Struck by the Ree was wrapped in an American flag by Lewis and Clark near the site of the future territorial capital, but journals of the famed explorers fail to mention the event. Even more controversial has been the chief’s name. Did he strike the Ree (Arikara), or did the Ree strike him? For purposes of this report, we’ll use Struck by the Ree from the treaty document and assume the story of his partial scalping by an Arikara warrior was true. However, another version says he avenged the murder of his brother by killing a Ree adversary with a spear. In that case, he supposedly earned the title of Strike-the-Ree.

George W. Kingsbury, who was at Yankton during the village years and knew the leader personally, used the latter name in his writings. Similarly, the Frost-Todd Trading Post Ledger, kept by George D. Fiske at the Indian camp in 1859, listed the Sioux leader’s account under the heading of “Strike the Rhee.”

Regardless of his proper name, his crucial role in the eventual settlement of whites in southeastern South Dakota remains. Unfortunately, for his involvement in the cession of land and subsequent removal to the reservation, Struck by the Ree was vilified by many of his own people for the rest of his life.

Even though his name was affixed to the treaty, Smutty Bear angrily challenged Struck by the Ree’s so-called surrender to the white man but Struck by the Ree prevailed. On the reservation, it was said malcontents constantly harassed Struck by the Ree. His cabin was burned, and his ponies were killed.

Lore also says a warrior named Aka once shot a gun loaded with a blank cartridge in Struck by the Ree’s face to show disdain for his actions.

To his credit, Struck by the Ree was a realist. Though he may not have wanted to see old traditions disappear, he recognized the inevitable change. He has been quoted as saying:

“The white men are coming like maggots. It is useless to resist them. They are many more than we are. We could not hope to stop them. Many of our brave warriors would be killed, our women and children left in sorrow, and still we would not stop them. We must accept it, get the best terms we can get, and try to adopt their ways.”

Despite opposition, Struck by the Ree continued to promote peace and industry among his people. He was credited with convincing his militant young warriors not to join the ill-fated Santee Uprising of 1862 while at the same time warning white settlers of potential danger. Later, he spoke regularly to assembled members of his tribe from the roof of his small cabin, encouraging them to work, learn and avoid physical confrontation.

He also preached the preservation of trees and other natural resources on the reservation. “If you do not save your timber,” he said, “the time will come when you will fish for driftwood and fight over it.”

For his efforts on behalf of peaceful white and Indian relationships, he received medals from three U.S. presidents: Franklin Pierce, Ulysses S. Grant and James Garfield.

Although he was baptized at an early age by Fr. Pierre Jean DeSmet, Struck by the Ree later came under the influence of Rev. John P. Williamson and adopted the latter’s Presbyterian faith. The Yankton leader, revered by some and hated by others, died on July 28, 1888, at the Greenwood Agency. Along with his medals, he was first buried on the edge of the Presbyterian cemetery established by Rev. Williamson.

Some 16 years later, his remains were moved to the center of the cemetery, and the exhumed medals were presented to his kinspeople. He apparently had five children, but there is little, if any, public record of his wife and immediate family.

Following his reburial, a granite monument was erected at his final resting place; it also added to the varied spellings of his name. Carved into the stone is a phonetic inscription in his native tongue: “Padaniapapi Huhu Tawa Den Wanka Ihanktonwan Iye Tokoheya Christian Wocekiye En Mniakastanpi.” Freely translated, it says, “Here lies the remains of Struck-by-the-Ree, the first Yankton to be baptized a Christian.” Also inscribed are the words: “He was in his day the strongest and most faithful friend of the whites in the Sioux Nation.”

Ironically, he has been largely forgotten by later generations. Sadly, the significant burdens he bore during the transitional years of cession and settlement have been too often overlooked or dismissed in history’s recording.

Undoubtedly, Struck by the Ree was a man of more substance than the later-day portrayal of him has reflected.

Sources

Yankton Daily Press & Dakotan; originally published Sept. 12, 1994. ©Copyright Yankton Daily Press & Dakotan