Nicholas Black Elk

“And while I stood there I saw more than I can tell and understood more than I saw; for I was seeing in a sacred manner the shapes of all things in the spirit, and the shape of all shapes as they must live together like one being. And I saw that the sacred hoop of my people was one of many hoops that made one circle, wide as daylight and as starlight, and in the center grew one mighty flowering tree to shelter all the children of one mother and one father. And I saw that it was holy.” – Black Elk

Heȟáka Sápa, commonly known as Black Elk, was a wičháša wakȟáŋ, heyoka of the Oglala Lakota people, and educator about his culture.

Black Elk witnessed the great Battle of the Little Bighorn in 1876 when he was 13. He was born on the Little Powder River in December 1863, the son of Black Elk and Sees the White Cow. Following the end of the Sioux wars, his family joined Crazy Horse in initially refusing to move onto the reservation; after finally yielding, Crazy Horse was killed. Black Elk and his family immediately fled to Canada where they joined Sitting Bull and his followers. The harshness of the winters and near starvation drove them back to the United States where they settled.

Black Elk is remembered for his many dreams and mystical experiences. The first of these occurred at the age of nine when he fell ill and layout unconscious for several days. He had a vision that seemed to predict the future of his tribe and his own role as a medicine man; he was disturbed by some of the things he saw but told no one. Eventually, more visions came, and finally, he told his father about them. By the time, he returned from Canada, his reputation had preceded him as a gifted medicine person, and he was sought after as a healer.

He traveled to Europe with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show and appeared before Queen Victoria during the celebration of her Diamond Jubilee in 1897. While in Paris, he fell ill and stayed with a French family. While recuperating there, he had a vision of his people back in America that compelled him to return immediately to the United States. Back in Pine Ridge, he found that Wovoka’s new Ghost Dance religion was gaining firm hold among the Lakota. Initially skeptical of the claims of invulnerability gained by wearing the decorated costumes, Black Elk subsequently had visions that seemed to support the Dancers, and he became a supporter.

In the early 1900s after the death of his wife, Katie War Bonnet, Black Elk converted to Catholicism, becoming a catechist while continuing to practice his traditional Lakota ceremonies.

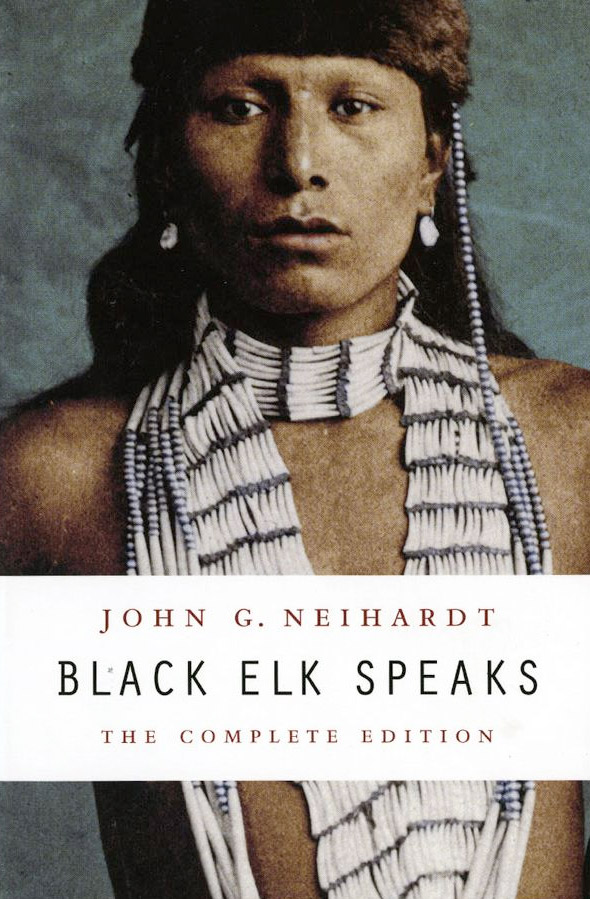

In the early 1930s, Black Elk told his religious views, visions, and events of his life in graphic detail to poet John G. Neihardt, a major figure in American literature. His son Ben Black Elk translated his stories into English as he spoke. The vision of Black Elk and the literary skill of Neihardt combined, produced the classic work in Black Elk Speaks: the Life Story of Holy Man of the Oglala Sioux.

Black Elk died on August 19, 1950, at Manderson and is buried at Saint Agnes Catholic Cemetery in Maderson, South Dakota.

A monumental tribute to Black Elk’s legacy lies in his sacred Black Hills–Pahá Sápa. On August 11, 2016, the US Board on Geographic Names officially renamed Harney Peak, the highest point in South Dakota, to Black Elk Peak to honor the mountain’s role in Black Elk’s vision and respect its spiritual significance to the Lakota people Black Elk symbolizes courage and wisdom for Indigenous and non-Indigenous people alike.

His ability to embrace Christianity while adhering to traditional tribal customs allowed him to bridge a gap and survive troubled times. His teachings spread far beyond his own people, and an impressive amount of literature details his life and beliefs. In 2017, the Western Catholic Diocese of Rapid City, South Dakota opened an official cause for Black Elk’s beatification as a saint with the Catholic Church, and some believe miracles are still being performed using Black Elk’s pipe.

Sources

Black Elk Speaks: The Complete Edition, by John G. Neihardt, Bison Books, 2004

The Sixth Grandfather: Black Elk’s Teachings Given to John G. Neihardt, edited by Raymond J. DeMallie, University of Nebraska Press; new edition, 1985

The Sacred Pipe: Black Elk’s Account of the Seven Rites of the Oglala Sioux, by Joseph Epes Brown, MJF Books, 1997