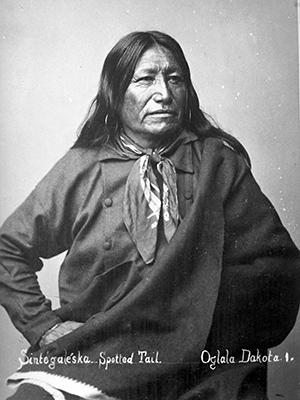

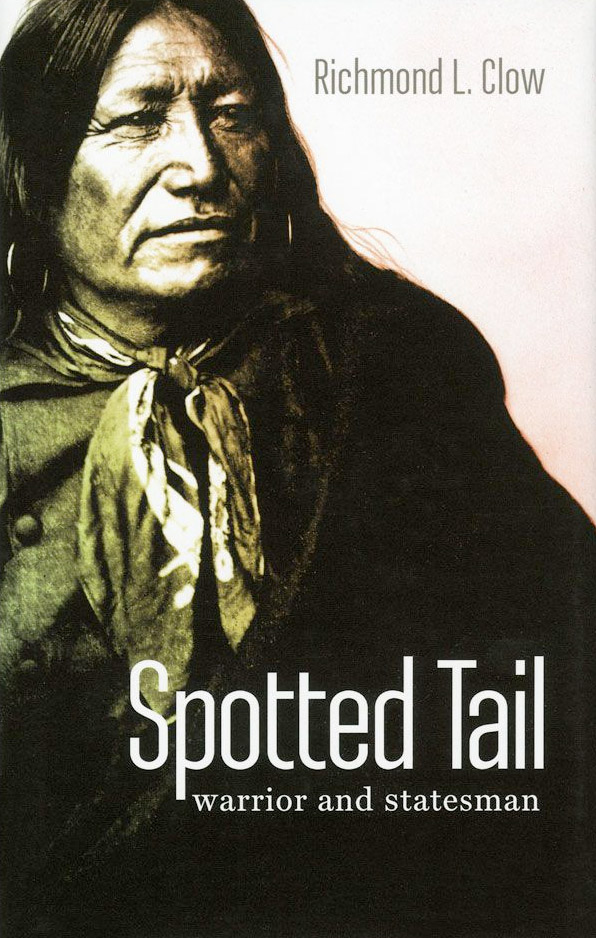

Spotted Tail

Siŋté Glešká was a Brule Sioux leader who became one of the most important individuals in the Northern Plains. He was born about 1823 along the White River in South Dakota (some accounts say near Fort Laramie, Wyoming). He was the son of a Saone man named Cunka (Tangled Hair) and a Brule woman, Walks with the Pipe.

Known as Jumping Buffalo in his youth, the future leader received his new name after a trapper gave him a raccoon. Spotted Tail was not a hereditary leader and gained fame through his integrity and ability. Renowned as a man of his word, he astounded Army officials on one occasion when he and two other Indian males accused of murder walked into Fort Laramie to give themselves up to spare the rest of the tribe.

During imprisonment, Spotted Tail learned to read and write English. Shortly after being freed, the tribe’s head leader Little Thunder died. The tribal leaders passed over the hereditary candidate and selected Spotted Tail.

Although he favored the Treaty of 1865, believing white settlement was inevitable, he and the other leaders did not sign the document. They were holding out for better terms. Their tactic worked, and in 1868, he signed the Treaty at Fort Laramie. In this treaty, the Sioux permitted railroad construction with the assurance they would be given a permanent reservation, including all of present-day South Dakota.

Spotted Tail made several trips to Washington during his lifetime. On each occasion, he learned more of the white man’s customs. When gold was discovered in the Black Hills, Spotted Tail and Red Cloud went to Washington to negotiate the sale of the mineral rights. Before leaving, Spotted Tail visited the land in question to learn the actual value of the minerals.

He listened carefully to miners and realized the mines were indeed of great value. When negotiations were opened and $6,000,000 was offered to the Indians, Spotted Tail demanded an amount ten times that for the mineral rights. This sum was unacceptable to the government, and no treaty resulted. Instead, the miners were allowed to enter the Black Hills without Army interference. Shortly after that, the Sioux found themselves overrun without any recourse to safe warfare.

Because Red Cloud was out of favor with the government, Spotted Tail was appointed head of all the Sioux at Rosebud and Spotted Tail Agencies. He was able to negotiate a peaceful arrangement which resulted in the surrender of his nephew, Crazy Horse, in 1877.

But, another force had been at work over several years. Black Crow, Crow Dog, and a few other Brule men were terribly jealous of Spotted Tail and were plotting to displace him. On August 5, 1881, Siŋté Glešká was shot and killed by Crow Dog. Siŋté Glešká was returning from a council meeting where he was elected to head for Washington an unprecedented third time.

The reasons behind the assassination and death are complex and controversial. In a landmark decision by the court, Crow Dog was eventually tried for murder and was freed because the courts had no jurisdiction over crimes committed on Indian reservation land. However, neither Crow Dog nor Spotted Tail’s son, Little Spotted Tail, were capable of leading the Sioux. The people were left without strong leadership at a critical time in history.

Today, Spotted Tail is buried at the Episcopal Cemetery in Rosebud, South Dakota. His gravesite overlooks the Rosebud Agency where the US Government and Brule people interact every day. Siŋté Glešká University also stands near as its mission embraces the lofty vision Spotted Tail had for his people.

Sources

Dockstader, Frederick J. Great North American Indians: Profiles in Life and Leadership. New York, NY: Litton Educational Publishing, Inc., 1977.

Hyde, George E. Spotted Tail’s Folk: A History of the Brulé Sioux. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1961