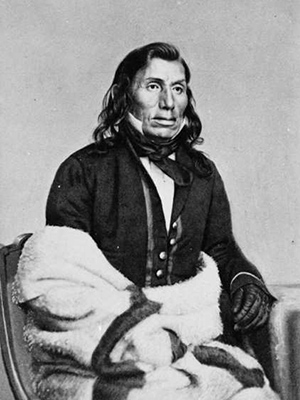

Little Crow

Little Crow was born in 1810 in the Mdewakantonwan Dakota village of Kaposia. He was the first son of Chief Wakíŋyatáŋka (Big Thunder). Little Crow grew to be an ambitious man and one without physical fear. He acquired a reputation of being a brave warrior. During these years, he also learned to read and write English.

After his father accidentally shot and killed himself in 1846, Little Crow became the leader of his band. Two of his half-brothers attempted Little Crow’s assassination shortly after that. However, they only succeeded in wounding him. Little Crow banished them, and when they returned, he had them executed.

When treaty negotiations began at Mendota, MN, in 1851, Little Crow’s people elected him as their speaker. When the negotiations were complete, he became the first leader to sign the Treaty of Traverse Des Sioux. Little Crow thought this treaty would enable his people to “never be poor.”

This was not the case. Almost immediately, trouble began. The government did not want the Sioux to own their own land, which was one of the stipulations in the original treaty.

Although they protested, the leaders had no choice but to sign a revised treaty. Traders, instead of the tribes, received part of the money from the land’s sale. These funds were to be held in “trust” for future purchases. However, the Indians never saw any returns from the money.

In 1858, Little Crow and the other lower Sioux leaders traveled to Washington DC, hoping to convince the government to redress the broken promises of the last treaty. Instead, the government threatened to take the land they wanted by force and coerced the chiefs into signing away a 10-mile tract of their reservation. Although Little Crow had spoken for the entire delegation, tribal resentment over signing the land away caused his popularity to decline.

During the following years, unrest among Little Crow’s people grew as the provisions and annuity money promised by the treaties was often too late, too little, or nothing at all.

Little Crow stepped in once again when news of the Spirit Lake Massacre committed by Inkpaduta and his band threatened to cause a war. He volunteered to lead a war party against Inkpaduta’s small band. In doing so, the group brought back four scalps and several women captives. Indian superintendent at the time, William J. Cullen, admitted Little Crow’s intervention helped avert the real possibility of war.

When the Sioux heard of the white man’s Civil War in the spring of 1861, they were very curious about what it would mean for them. Some worried the Confederates would enslave the Indians if they won.

Tensions among the Dakota increased in the summer of 1862 when the annuity payments were not made on time. In August, starving Indians broke into the agency warehouse. They forced the Indian Agent, Thomas Galbraith, to give them provisions. The tribe soon called for the election of a new speaker. They felt Little Crow had failed them.

However, four days later, on August 17, Little Crow awoke to terrible news. Four young Wahpetons had killed several white men and women at the Acton Post Office. The tribe needed Little Crow’s experience with the white men to handle the situation. Little Crow knew the white men would take vengeance for their slain women. The chief had only two plausible options: turn over the murderers, or go to war.

After much discussion, the leaders discarded the first option. The issue of war divided them. Wabasha, Traveling Hail, Taopi and Wakute opposed war. Big Eagle, Red Legs, Mankato, and Little Six supported the war.

Despite all of the confusion, Little Crow led several warriors to the Redwood Agency early the following day and killed about 20 white men. This action began the Dakota Uprising. Many of the Dakota began rampaging across the countryside, killing white settlers. Little Crow disapproved of killing people who had not harmed them and pleaded with the warriors to spare the women and children.

Little Crow led ineffective attacks on Fort Ridgely. He led the attack on New Ulm and succeeded in burning most of the town. Then, he raided Hutchinson and Forest City.

When Henry Sibley’s army arrived in Yellow Medicine, where the Dakota camped, Little Crow knew this could be the last fight. On September 23, the Dakota attacked and were driven back by Sibley’s skirmishers, mostly Civil War veterans. Mankato was among the 30 Indians killed.

Little Crow could no longer rally the warriors. He retreated up the Red River with some of his people. He continued his attempts to rally support among other bands but had little success.

On June 10, 1863, Little Crow left his sanctuary at Devil’s Lake, ND, to raid Minnesota. He went to gather horses for himself and his family. He took several men and one woman with him. The group soon split up, leaving Little Crow and his 14-year-old son alone in the “Big Woods.”

On the morning of July 3, 1863, Little Crow and his son stopped to pick raspberries near Hutchinson. A settler named Nathan Lamson spotted the two Indians while he was hunting with his son. Lamson shot and killed Little Crow. His son was injured but managed to return to his people at Devil’s Lake. He was later captured and sent to Davenport, Iowa, where he converted to Christianity and took the name, Thomas Wakeman.

He became the founder and first Secretary of the YMCA among the Sioux. He had four sons and two daughters: Solomon, Ruth, John, Jesse, Ida, and Alex. Ida discovered her grandfather’s bones hanging in a Minnesota museum. She returned home and told her brother, Jesse, who fought for the return of his grandfather. Eventually, the bones were returned to the Wakeman family, and Little Crow was buried in 1971.

Sources

Diedrich, Mark. Famous Chiefs of the Eastern Sioux. Minneapolis: Coyote Books,1987: 62-75. Hughes, Thomas. Indian Chiefs of Southern Minnesota. Minneapolis: Ross&Haines, Inc. 1969: 52-58.